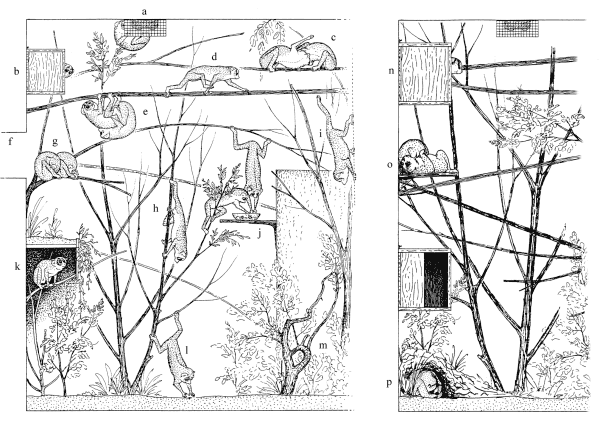

Examples for the use of

adequately

furnished cages.

(The figure does not show

normal

population density!)

| Home |

|

|

|

Examples for the use of

adequately

furnished cages.

(The figure does not show

normal

population density!)

Left: Loris tardigradus

If

lorises are disturbed or frightened, they usually go up as high

as possible,

for instance clinging to a wiremesh ceiling in hanging posture

behind some

cover (a). Some animals prefer to hide in boxes (b)

when

disturbed, some like to sleep in boxes or hidden between leaves,

but often

Loris

sleep in the open. Energy-saving stay on top of horizontal

branches is

characteristic for most behaviour of the Loridae, particularly

for resting

and comfort behaviour ( c: allogrooming). d:

Longer horizontal

branches in Loris encourage a fast, trot-like locomotion

which is

seldom seen on irregular substrate. e: Substrates in the

upper part

of the cage allowing hanging postures (thin horizontal branches,

wiremesh)

are important for sexual behaviour. f: Passages to

neighbouring

cages have several advantages: they allow easy separation of

animals, cleaning

of cages without animals inside, they are frequently used by the

animals

for having a look at the environment and considerably promote

locomotor

activity.

g: For sleeping, places

with a lateral support are appreciated. h: Vertical

substrate is

used for climbing up and down. i: Wiremesh, both

horizontal and

vertical, is a valuable substrate for climbing. Wiremesh walls

can help

to assure continuous locomotor opportunities without "dead end"

branches.

j:

Food ought to be offered in an elevated place; for shy animals,

some cover

close to the feeding places is helpful. k: In cases of

quarreling,

frightened animals go down and try to hide; shelters protecting

the refugee

against sight from above can diminish social stress. Such

hideaways ought

to have a second exit allowing escape from aggressive

conspecifics.

l:

Live insects on the floor promote climbing and hunting. m:

The use

of the lower parts of cages can be improved by undergrowth.

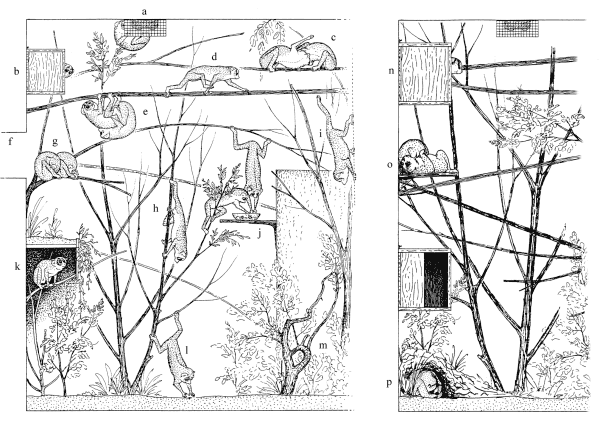

Right: additional

recommendations

for Nycticebus cages.

In both slow loris species,

sleeping

boxes (n), tubes or other hollow hideaways or dense plant

cover

around comfortable sleeping branches are apparently more

important than

in Loris . Boxes must be large enough for the group;

additional

boxes in lower parts of the cage or even on the gound have been

readily

used by some groups under normal conditions, with no evidence

for social

stress (Fitch-Snyder; Schweigert, pers. comm.; Lippe, pers.

comm.). If

the temperature is very warm, N. coucang at San Diego

Zoo like to

sleep flat on their backs on a shelf (o); in N.

pygmaeus,

lying on the back while sleeping has not been observed

(Fitch-Snyder, pers.

comm.). N. coucang in the wild have been found walking

on the ground

or sleeping hidden under leaves on the ground (Wiens, pers.

comm.); in

captivity, sleeping on the cage floor, hidden under newspaper,

straw, towels

or other available substrate also occurs in N. coucang .

N. pygmaeus

at San Diego Zoo prefer sleeping on top of straw and in higher

parts of

the cage, but in other facilities they also regularly sleep on

the floor,

in boxes or hidden under substrates (Fitch-Snyder; Schweigert,

pers. comm.).

In N. pygmaeus, after sleeping period cases of

hypothermia (cold

body, abnormal movements and equilibrium problems or animal even

lying

on the ground, showing little reaction) have occurred. A

sufficiently high

temperature of all potential sleeping places (including the

floor) seems

necessary (Schulze 1998; Schweigert, Lippe, pers. comm.).

Recommendations

for

cage furnishing: Under

normal conditions, the upper part of the cage is highly

preferred, but

use of the low parts can be improved if some undergrowth is

provided. In

periods of social stress, inferior animals try to avoid the

superior aggressive

conspecific and go to the lower parts of the cage as long as

they feel

threatened, staying there quietly or trying to hide under some

cover. Adequate

facilities for a stay close to the ground therefore are

necessary.Thin

climbing substrate, tightly fixed, stiff or elastic

(recommendation: at

least 15 m) is needed. Urine-absorbent timber perches and

natural branches

are an adequate substrate for olfactory marking. Branches ought

to be attached

in a way allowing continuous locomotion. This may be assured for

instance

by vertical branches attached close to the ends of horizontal

ones, by

branches in close proximity allowing bridging between them, or

by wiremesh

cages which allow locomotion along walls or ceiling. "Dead end"

branches

and narrow passages not allowing animals to give way to

conspecifics may

cause or aggravate quarreling.

In cages with smooth walls

which

do not allow satisfactory attaching of branches, a good

furnishing can

be achieved by a supporting framework, made of a few vertical

perches to

which horizontal ones are tightly fixed with wire. Horizontal

substrate in the upper part of the cage, thin enough to allow a

safe attachment

with hands and feet, is necessary. Unlike Tarsius , Loris

has got no tail supporting the body weight during clinging to

vertical

stems and therefore needs horizontal branches for energy-saving

resting

and moving on top. Hanging postures under horizontal substrate

(branches

or wiremesh) are important for comfort, social and sexual

behaviour.A cage

allowing active influence on the animalsī situation by some

behaviour

is one of the best preconditions for wellbeing. Hideaways may

allow some

influence of the state of environmental distress. A high place

with some

cover (foliage, nest boxes) where the animals are never

disturbed may give

them the feeling to be safe. In the colony at Ruhr-University,

disturbance

in such areas is avoided by particular facilities for catching

animals

(for instance a baited cage which can be closed by pulling a

thread) and

by allowing access to play facilities when the cages have to be

cleaned.Although

captive lorises show a highly developed social behaviour and

considerable

social needs, in the wild they probably lead a rather solitary

life. Some

privacy, if desired, might be provided by some sort of

partition, optical

separation by plants, parts of the cage which can only be

reached by locomotion

over longer distances or access to which is a bit difficult, and

by hideaways

in places used seldom under normal conditions. Transmitter

collars selectively

allowing certain animals to pass shutters might be a perfect

solution.

In very large cages, some free space may provide more privacy;

in smaller

cages, however, particularly in the preferred upper part of the

cage no

space ought to be wasted for this purpose. Of

course, working procedures must be considered in cage design;

free access

to the cage for cleaning and other work is necessary (B. Uphoff,

pers.

comm.). Possibilities to spread a plastic foil at least on a

part of the

ground for collecting urine and faeces samples may be helpful

for health

control. Possibilities of cheap and easy behavioural enrichment

might be

considered in planning of the cage (G. Heuss, zoo architect,

pers. comm).

Substrate preference

Substrate use

Inadequate cage furnishing:Vertical trunks and branches with a large diameter do not allow a safe grip; chutes from such substrate have been observed. In two animals, healed bone fractures were detected. Tree trunks can be improved by inconspicuously attaching some wiremesh or lianes for climbing up and down. Swinging substrate such as ropes and loose perches turning round or rattling when the animals try to walk on them are inadequate although they may occasionally be used, particularly by playful youngsters. Rattling noise of loose perches in addition resembles the noise caused by sudden flight of frightened lorises or by locomotor display of very aggressive conspecifics and therefore causes stress reactions. Flat ground is occasionally used, but hands and feet are adapted to a grip around some substrate. In tests, lorises apparently did not like standing on a flat surface, but chose a possibility to flex their toes around at least one edge if possible.

Nest boxes or nesting material : In cases of disturbance, many animals use wooden boxes in the upper part of the cage as a hideaway. Sleeping in such boxes regularly occurs as an individual habit of some rather shy animals; most lorises usually sleep in the open or hidden in foliage. At low altitude, half-open or open hideaways are better than closed boxes with only one entrance because such places are used in cases of social stress when an escape from conspecifics may be necessary. Nesting material is neither needed for sleeping nor for rearing of offspring although on rare occasions, for instance, some draping of cloth and sleeping behind it has been observed. In pottos, a kind of "nest-building" on the floor has been mentioned (Cowgill, 1969); sleeping on the ground, hidden under dead foliage (Wiens and Zitzmann, pers. comm.) or wrapped in paper (Schweigert, pers. comm.) regularly occurs in slow lorises and pottos, but in the lorises at Ruhr-University no such behaviour has ever been observed.

Cage design encouraging physical training : A fast, almost trot-like locomotion, particularly by young Loris males, is almost exclusively seen on longer, straight, horizontal branches whereas irregular substrate rather seems to encourage slower climbing. Lorises, and particulary the males, often show a considerable amount of locomotor activity; correspondingly Rasmussen (1986) came to the conclusion that in captive Nycticebus "... most of the traveling observed ... did not seem to be directed to a specific goal; usually lorises circuited the room just for the sake of locomotion". On the other hand, cages mainly equipped with the preferred, comfortable horizontal substrate apparently promote indolence and adiposity in some individuals; some substrate gaps which promote bridging, feeding places or lookouts which can only be reached with some effort, longer passages outside cages or between two cages providing a view on the surroundings, or two cages connected by a longer passage may promote locomotion.

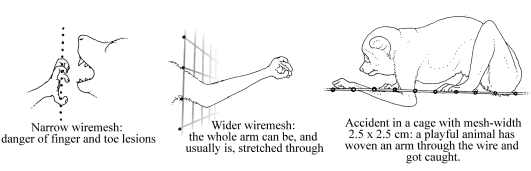

Danger of accidents due to inadequate cage furnishing: In spite of relatively cautious locomotion, lorises occasionally fall down from branches; healed bone fractures have been found (Plesker, pers. comm.). Sharp edges on the gound and deep water may therefore be dangerous. Lorises are said to be unable to swim (Roonwal, Mohnot, 1977); Ryley (1913) wrote: ""They appear quite unable to swim and when placed into water would strike out alternately with each leg in a helpless way without making any headway". No tests in this regard were made at Ruhr-University. During quadrupedal locomotion, nostrils are usually few cm above the branch surface; in tests with dead lorises, the maximum possible altitude of nostrils above ground, with the arms extended and muzzle pointing upwards, was 16 to 20 cm (15.5 cm in a small reddish specimen). Loose threads are dangerous because lorises like to use them as objects for playful clutching and may strangle themselves; threads hanging outside wiremesh, but within reach of the animals are usually pulled into the cage. In rare cases, animals have jammed themselves by stretching an arm through wiremesh, as shown in the figure, or by stretching a hand through a cleft which was narrower below than above; an open hand can be stretched through a cleft of about 7 mm, a fist through a cleft of 8-10 mm; after a rotation of 90°, the same fist needs about 12 mm space to be drawn back. Biting into of parts of the cage or cage furnishing occurs as a play behaviour or due to boredom; genuine and artificial plants were chewed, and some wood showed deep tooth marks. Electric cables, poisonous plants or colours might therefore be dangerous. Some of our lorises developed a considerable ability to open doors and shutters to escape; fighting with inhabitants of other cages may be the consequence.

Danger of accidents in cages with a certain mesh-width: Clinging to wiremesh of an opponentīs cage may lead to fighting and severe finger and toe lesions. With increasing mesh width, the danger that an arm is stretched through and comes within reach of hostile conspecifics in the next cage increases; threads and thin electric cables outside the wiremesh may be seized and pulled in, causing some danger for the animals which may strangle themselves (one case reported from a zoo), and accidents as shown in the right figure may occur.