Lorises have a

| Home |

|

|

|

Content:

Detection of

lorises in the field. Eyeshine, sympatric species, search stretegies

Sources of light recommended for field use

Visible behaviour: movements

helpful for identification of species; protective behaviour

(flight, camouflage)

Vocalization

Traces

Indiviadual identification, recognition

marking

Survey/census methods

Literature

Detection

of lorises in the field

Handrearing lorises and pottos

Coauthors: Helga Schulze. (Ruhr-University Bochum), Helena

Fitch-Snyder (Loris Conservation International), Anna Nekaris

(Nocturnal Primate Research Group), and Mewa Singh (Mysore

University. Includes data by Janet Hawes, San Diego Zoo, Jackie

Ogden, Disney´s Animal Kingdom, Kissimee, FL., Sarah Christie,

London Zoo, Carol Sodaro, Brookfield Zoo, B. Meier and U.

Nieschalk, Ruhr-University. See also acknowledgements and

references.

Information partly also published in: Schulze,

H., Ramanathan, A., Fitch-Snyder, H., Nekaris, K.A.I., Singh,

M., and Kaumanns, W., 2005: Care of rescued South Indian

lorises with guidlines for hand-rearing infants. Pp. 104-118 in:

Menon, V., Ashraf, N. V. K.; Panda, P.; Mainkar, K. (eds): Back

to the Wild: Studies in Wildlife Rehabilitation. New Delhi:

Wildlife Trust of India.

For more information see the handrearing

chapter of the San Diego loris husbandry manual.

Update in preparation, available here soon, with information about milk composition, rearing techniques, weight development and, as far as available, information how to determine the age of rescued or confiscated orphaned infants

Content:

When is handrearing necessary?

Lorises have a

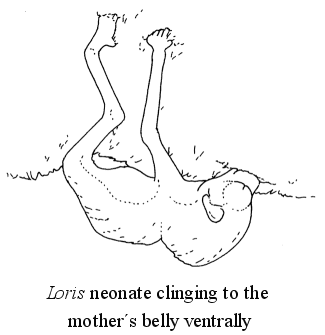

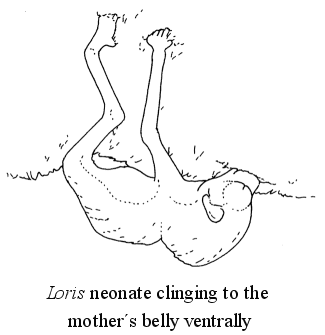

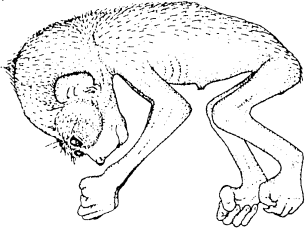

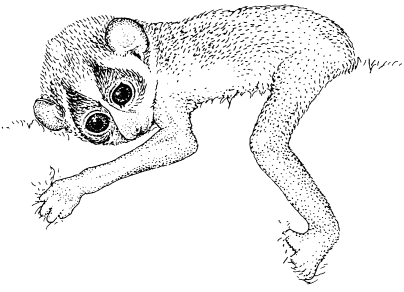

Slender loris babies usually cling to the mother permanently during the first weeks, unlike in Nycticebus and pottos from whom regular infant parking is reported. Loris babies may occasionally fall down from their mother; they will then give zic calls (short high clicking or chirping calls) which cause the mother to search for the baby and either pick it up or stay close to it until it has mounted again. Experience at Ruhr-University showed that babies who have fallen down repeatedly from the mother in the first two weeks after birth, utter zic calls permanently or are repeatedly torn away from the body and held at soome distance from the body by the mother usually will not be successfully reared, even if the mother carries them with her hands for longer periods, either because she has no milk and they fall down because of increasing weakness (permanent crawling about on the mother may be a sign of searching for milk) or because they were hurt during a chute and are therefore unable to cling to the mother´s fur properly. In one case, a two-weeks-old infant with seizures after falling down and hitting a branch was kept on electrically heated fur and fed for 24 hours until seizures and permanent zic calls stopped and was then successfully reintroduced to mother and twin sibling. Hawes and Ogden (in press) recommend to try supplementation of mother-reared infants with formula if the mother has got too little milk or cross-fostering (introducing infants to an other mother with milk) and early introduction of handreared infants to conspecifics.

If reintroduction to the mother is tried, avoiding of any

disturbance by humans is necessary because the mother may become

extremely excited and nervous already from hearing repeated zic

calls; even sham-attacks with growling against the baby have been

observed in such cases, shy mothers did not dare to approach a

baby lying in lower parts of the cage when disturbed by observers,

and in one case the excited mother tore the healthy twin sibling

from her fur, too, and dropped it with excitement. Retrieval by

the mother may be made easier by depositing the baby in a high

place where the mother feels safer; covering the floor below with

something soft below (cushion) may then prevent lesions if the

baby falls down again.

Housing during first weeks of handrearing:

Some surrogate imitating the mother´s body (artificial or genuine

fur, plush animal) is necessary for the infant´s wellbeing. Hawes

and Ogden (1998 / in press) recommend prewashing of surrogates and

use only of those not continually shedding and simulation of

maternal body temperature by a hot water bottle; they also

recommend additional use of blankets as a hiding place. At

Ruhr-University, an electrical heating pad rolled around a stick,

kept at 37°C and covered with soft fur, was used; it was attached

in the cage in a way allowing the baby to cling to it from below

as well as on top. At the age of 100 days the loris did not sleep

on it any more but on a branch. Temperature was 22-27°C (with

infrared light outside the cage), some protection against draught

(plastic foil) was provided and air humidity was kept at

approximately 80% by a wet towel in the cage. When the infant

began to climb, additional thin branches were provided (Nieschalk

1984). At London Zoo, an incubator providing a temperature of

33-35°C was used, a water tray beneath wiremesh kept the air humid

(Christie, 1992). For occasional transports, at London Zoo an

insulated travelling box with pre-heated heating pad isnside was

used. For a lesser slow loris neonate, an incubator temperature of

32.2°C was initially maintained; from day 21 on temperature was

gradually reduced to 25 - 25.6°C at day 39, with a toy animal

provided to cling to. On day 46 the animal was transferred to a

small mesh cage furnished with branches and other surrogate

allowing contact to both parents through the wiremesh, with access

to the dam´s enclosure through a little door from day 60 on. At

San Diego Zoo, an incobator with 32°C and humidity set low is used

(at Philadelphia Zoo humidity is set high), between approximately

day 19 and 47 incubator temperature is diminished to 27°C and the

infant is gradually habituated to stay outside the incubator. For

Nycticebus babies offering of branches from the fifth day

on is recommended for simulation of natural infant parking, with

branches preferably taken from the cage of the infant´s natal

group (Hawes and Ogden, 1998 / in press).

Feeding procedure and care:

For slender loris babies, catheters fitted to syringes turned out to be a good nipple substitute, commercially available teats proving too big. For handrearing a lesser slow loris at Brookfield Zoo, a tuberculin syringe fitted with a latex nipple which had been produced in-house.. An additional 0-05 ml of formula was added to each feed to compensate for the amount of liquid that remained in the syringe tip (Sodaro, 1993). Hawes and Ogden (1998 / in press) during the first days recommend special attention to avoiding aspiration of formula into the lungs, particularly in Loris neonates because of their frequent vocalization and active nature.

For later use, small size nipples may cautiously be tried; multi-purpose small teats # T-3 available from Geoff and Christine Smith, 15 O´Shannassee St., MT. Pritchard NSW, Australia, are recommended by Hawes and Ogden (1998 / in press)

Wiping of the infant´s genitals with a wet cloth or soft hair-pencil after feeding stimulates urination and defecation during the first month. Defecation in the Loris baby at London zoo also took place without stimulation whereas urination had to be stimulated; at Ruhr-University, no independant urination or defecation was observed until about day 70. In a potto, stimulation was necessary for two months, then the juvenile ceased to respond (Walker, 1968).

Cautious grooming of the fur with a soft little brush,

particularly in the arm pit / median upper arm region (brachial

gland fields), is apparently enjoyed.

Milk composition, feeding intervals

For loris handrearing, diet still seems to be a problem; of two slender lorises successfully handreared one had to be euthanized at the age of about 18 months because of severe diabetes, the other one had eye problems (decreased vision) at a rather young age and had to be euthanized because of untreatable eye ulcera at the age of six years.

For primates in general, Gass (1987, quoting Tiemann 1985) recommends not to change the formula product used. At London Zoo (3-days-old baby), during the first 5 hours glucose solution (5%) was offered against dehydration; a total of 0.45 ml was taken in three feeds. Then SMA liquid (human baby milk by John Wyeth & Brother Ltd., Maidenhead, Berkshire, Great Britain), at half strength for the first six feeds on day 4, then full strength until day 9 was given. Since according to Jenness and Sloan (1970) slow loris milk is higher in protein and fat and lower in carbohydrates than SMA and little weight gain was measured, then a mixture of SMA and Multimilk (milk powder high in protein and fat, manufactured by PetAg Inc., 201 Keyes Avenue, Hampshire, Il. 60140, USA) was gradually introduced over several days (Christie, 1992). Since problems (see below) indicated that this diet was still inadequate, a richer diet as used at Duke University Primate Center (K. Weisenseel, pers. comm.) was then provided; this change and later further concentration by reduction of the amount of water alleviated symptoms such as distended belly, copious urine and occasional vomiting after meals.

Composition of fresh milk of lorises and some other species

| Dry matter / total solids (% of fresh milk) | Fat (% of fresh milk) | Protein (% of fresh milk) | Carbohydrates / sugar (mostly lactose, % of fresh milk) | |

| Nycticebus sp., slow loris | 16.5 | 6.99; 11.8 | 3.9 | 6.6 (lactose: 6.2) |

| Loris, slender loris | 16.3 | 4.0 | 7.1 | 1.23 |

| Human | 12.4 | 3.8; 4.5 | 1.1 | 7.0 (lactose only) |

| Cow (different breeds) | 13.1 - 15.0 | 4.1 - 5.5 | 3.6 - 3.9 | 6.8 - 7.0 (lactose only) |

| Cat | 25.4 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 3.4 (lactose only) |

| Dog | 20.7 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 3.7 |

Sources: loris milk: Jennes and Sloan 1970; Myher et al. 1994; Tilden and Oftedahl 1997. Loris: based on only one sample. Other species: from Hurley (undated).

Milk of Nycticebus for instance is a high energy milk

with a rather high content of fat (Tilden and Oftedahl 1997).

Commercially available milk replacers for

handrearing mammals include products for human babies, for rearing

dogs and kitten (available in local pet shops) and milk replacer

systems, for instance Zoologic® Milk Matrix by PetAg (website: http://www.petag.com/) which

can be blended for closely matching the milk of different mammal

species, with supplements like certain amino acids and intestinal

flora available.

Milk replacers used for loris handrearing

Human milk replacers:

Initial check: animal dehydrated: see first aid chapter in the

loris and potto conservation database,

PetAg recommends slight underfeeding with milk replacers in the

first two days to allow the baby to adapt to the new food (PetAg

brochure: “Emergency care - a guide to saving little lives” (PDF

file,

http://www.petag.com/products_items.asp?SubcategoryID=31&CategoryID=8);

Hawes, Ogden 2001: During initial feedings the animal’s hydration

and blood glucose levels must be monitored closely. If the animal

is dehydrated or hypoglycemic, some institutions combine formula

with electrolyte solution such as Pedialyte (oral electrolyte

maintenance solution for replacing liquid in human children with

diarrhoea) or D5W (5% dextrose in water). Others supplement with

subcutaneous fluids.

Examples, applied:

Initially treated with Ringer´s solution (solution containing the

chlorides of sodium and potassium and calcium that is isotonic to

animal tissues) (Daffner + Daffner-Ellinger, pers. comm.)

Mixture of esbilac and pedialyte 1:1 successfully used (Sodaro

1993)

Initially (age 3 days) 5% glucose solution against dehydration

over 5 hours, then SMA liquid: half strength for six feeds, 10

hours (Christie 1992)

Slow lorises / general: liquid esbilac and distilled water, amount

of water decreasing (Hawes, Ogden 2001)

Loris; Nieschalk 1984: normal human baby formula: Milumil,

Preaptamil, Aptamil, Milupa Bananenbrei the animal had to be

euthanized because of diabetes at the age of 18 months (possibly

not because of milk composition, but because of too many titbits,

animal as an adult was extremely fat)

Christie 1992: SMA liquid: human baby milk

N. pygmaeus, N. bengalensis, Ellinger + Daffner-Ellinger, pers.

comm, successful (initially normal human milk replacer, later

"Humana Heilnahrung", a commercially available human baby food for

treating diarrhoea, pancreatic insufficiency and dysfunctional

gall secretion, with low fat content, a special fat named MCT and

high fiber content, for feeding in addition to other nutrition)

Slow lorises / general: liquid esbilac and distilled water (Hawes,

Ogden 2001)

Commercially available animal milk replacers:

Esbilac by PetAg (Sodaro 1993).

Inadequate: Milk replacer with low fat: skim milk (defatted milk):

successfully used for lemurs, but not rich enough for lorises

Supplements added to milk formula:

50% dextrose solution, half a drop to every third meal (Sodaro

1993)

Usually added: multi-vitamin drops

Calcium?

Iron: added (Sodaro), but see danger of hemosiderosis in

prosimians

Field observations indicate that Nycticebus infants are

parked for longer periods and not fed at short intervals as usual

in captive handreared infants (Wiens, pers. comm.), but more

frequent feeding might be necessary during handrearing as lower

weight gain from artificial formula than in mother-reared infants

was observed, for instance by Christie (1992).

| London (Christie, 1992) | Meals | Bochum (Nieschalk 1984) | Meals | ||

| Age | Food consumed | (formula) | Age | Food consumed | (formula) |

| Day 3 | 0.45 ml per day (glucose) | 3 (total) |

|

(mother-reared) | |

| Day 4-5 | 5.25; 6.4 ml per day | 15, 10 per day |

|

(mother-reared) | |

| Day 6-11 | 5.4 - 9.4 ml per day | 9 per day | Day 9- | Milumil (or Preaptamil

or Aptamil); as directed by makers, lactose added

to every third meal, calcium (Osspulvit) twice per

week and vitamin (Multibionta) added. Quantity: as

much as the animal would take (E. Zimmermann, pers.

comm). From day 84 on Milumil mixed with the same amount of milk protein powder (Protifar); no more lactose. |

|

| Day 12 - 41 | 5.2 - 9.9 ml per day | 6 - 9 per day | Day 14-56 | Every 2 hours | |

| Every 3 hours | |||||

| Day 42-45 | 8.4 - 10.9 ml per day, first mashed banana | 5 - 6 per day | Day 57-69 | ||

| Every 5 hours during night, every 3 hours during day | |||||

| Day 46-50 | 11.4 - 13.9 ml per day, mashed banana regularly taken | 4 - 5 per day | Day 70-84 | ||

| Day 51-68 | 13.6 - 18.7 ml per day, milk concentration increased twice |

4-5 per day | Day 85-120 | Fruit offered in addition; consumption of solid food from day 100 on | Every 4-5 hours |

| (Mother-reared loris: first seen feeding from mother´s dish at day 64) | (Mother-reared loris: consumption of solid food starting between the 75th and 120th day; data by B. Meier). | ||||

| Day 69 - 80 | 9 - 18.3 ml per day, additional banana-pellet-mix |

3 per day | From day 140 on | Insects offered in addition | Twice per day |

| Day 81 - 111 | 16.7 - 3.5 ml per day, from day 109 on weaning, amount of formula decreasing. Insects added to diet | 2 - 3 per day | |||

| After day 111 | No more formula handfeeding; adult diet | ||||

* Esbilac containing 15.2% solids, 6.5% fat, 5% protein and 2.4% carbohydrates. Pedialyte = electrolyte solution. One to two drops of Polyvite multi-vitamin iron supplement were added to each 100 ml of formula. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Age, days | Diet | Meals (formula) |

| Days 1-21 | One part evaporated milk, two parts water as recommended by Crandall 1964, one drop multivitamin (Abidec, by Parke-Davies, Great Britain) per 14 g | Every 3 hours during day, once per night |

| Day 21-120 | ||

| Every 3 hours during day, no feeding during night | ||

| About day 35 | First solid food taken (mashed paw-paw) | |

| About 6 months | First live prey taken; almost all live and vegetable food taken from then on, main diet: banana, shredded beef, milk |

Observed health problems during hand-rearing:

Cooling down after separation from he mother: occurs quickly in neonate slender lorises with their thin hair cover (observation at Ruhr-University at normal room temperature). Thermoregulation in Nycticebus begins to work approximately at day 19 or 20 (Hawes and Ogden, 1998 / in press)

Dehydration or hypoglycaemic condition: may be treated with addition of Pedialyte or D5W to formula or with subcutaneous supplementation of fluids (Hawes and Ogden (1998 / in press)

Intermittently-occurring mild diarrhoea, over-extended belly, emission of abundant urine, occasional vomiting after feeding: condition improved after giving more substantial, less diluted formula (Christie, 1992)

Spasms on day 4 (infant passing clear bubbles from the mouth and hiccuping excessively during feeding. Suspicion that the amount of food given exceeds stomach capacity; frequency of feeding therefore increased too one-and-a-half hours intervals and amount per feed decreased (Sodaro, 1993)

Walker (1968) also observed three attacks of painful cramp in a successfully reared potto in which it was unable to extend its digits. The attacks passed of in half an hour.

Signs of constipation were frequently in the loris reared t Ruhr-University; time of genital / belly massages was then prolongued and more lactose was added to the food. When this did not help, warm hip-baths (approximately 37°C) of a duration up to 20 minutes were given, combined with an enema with babylax, and more liquid (Fennel-tea) was given (Nieschalk 1984).

At the age of 3, 6 and 9 weeks a thick white coating was found in the oral cavity of the slender loris at Ruhr-University, in the first case leading to difficulties with breathing. In all cases E. coli were found, in one case in addition Klebsiella oxytaka, and in two cases fungi. Medicine was chosen after resistance tests (Nieschalk 1984).

Treatment:

1st case: Minocyclin (antibiotic), 0,2 mg per day for five days; at the same time Candio-Hermal (antimycotic), three times per day for 7 days, each time 1 - 2 drops.

2nd case: Sulfonamid / Trimetoprim, 0,2 mg per day for 7 days; from the 5th day on in addition Candio-Hermal, 2 - 3 times per day for 6 days, each time 1 - 2 drops.

3rd case: Minocyclin, 0,3 mg per day for three days

The medicaments helped and were tolerated by the animal.

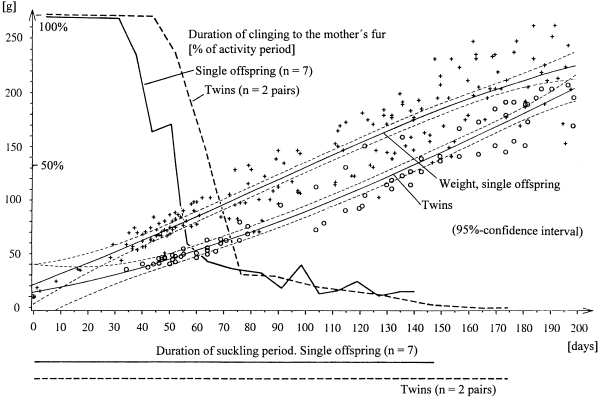

Infant

development in L. t. nordicus

|

|

|

Behavioural and weight development in captive-bred mother-reared single offspring and twins of L. t. nordicus from Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. Data: B. Meier

References:

Brown, C., 1979: Handrearing Senegal bushbabies Galago senegalensis at the Wildlife Breeding Centre. International Zoo Yearbook 19: 261-262

Christie, S., 1992: Hand-rearing a slender loris, Loris tardigradus nordicus, at London Zoo. Int. Zoo Yb. 31: 157-163.

Crandall, L. S., 1964: Management of wild animals in captivity. Univ. of Chicago Press. (Pp. 74-82: Family Lorisidae. Lorises, pottos, and galagos).

Gass, H., 1987: Affen. Pp. 1-43 in: Krankheiten der Wildtiere [diseases of wild animals], Gabrisch, K.; Zwart, P. (eds.), Schlütersche , Hannover. (German)

Hawes, J.; Ogden, J., 1998 / update in press: Birth management and hand rearing. In: Fitch-Snyder, H.; Schulze, H.; Larson, L. et al.: Management of Lorises in captivity. A husbandry manual for Asian Lorisines (Nycticebus & Loris spp.). Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species, Zoological Society of San Diego, Box 551, San Diego, CA 92112-0551.

Jennes, Sloan, 1970: The composition of milks of various species: a review. Dairy Sci. Abstr. 32: 599-612.

Nieschalk, U., 1984: Haltung und Verhalten eines handaufgezogenen Loris tardigradus. [Care and behavioural development during handrearing of a Loris tardigradus]. Unpublished report for the DFG (German Science Foundation). Ruhr-University Bochum. (German)

Sodaro, C., 1993: Hand-rearing and reintroduction of a Pygmy slow loris, Nycticebus pygmaeus, at Brookfield Zoo, Chicago. Int. Zoo Yb. 32: 221-224

Walker, A., 1968: A note on handrearing a potto.

International Zoo Yearbook 8: 110-111.

| Slender loris husbandry information

Preliminary draft; H. Schulze |

Last amendment: 22 November 1999 |